Debates about whether we are in a constitutional crisis have reached a fever pitch. Many citizens are concerned about whether our democracy will endure in a way I have never seen. In this two-part essay series, I aim to help you think about what counts as a “constitutional crisis” and if we are really in one. In this first essay, I will give you a definition of “constitutional crisis” to help you make sense of competing arguments about the state of American democracy and explain what constitutional crises have looked like throughout American history. In the second essay, I will explain whether we have descended into a constitutional crisis under President Trump’s leadership.

Why should you listen to me when so many others are writing about whether we are in a constitutional crisis? First, I am a legal scholar who teaches courses about state constitutions and the U.S. Constitution. In school, many of us only learn about the U.S. Constitution. However, we have 50 other constitutions in America. These state constitutions can teach us things about American constitutional law that we wouldn’t learn by studying the U.S. Constitution. At the same time, I have spent years thinking about and teaching the history of American constitutional law that should guide our thinking about how to know whether we are in a constitutional crisis.

Second, I have been studying constitutional crisis since 2013. That year, as a law school student, I researched Arkansas’s elections in the 1870s. I became hooked when I learned about the Brooks-Baxter War. After a disputed election where the losing candidate, Joseph Brooks, claimed to be the victim of fraud, he eventually raised a militia, and kicked his opponent, Elisha Baxter, out of the governor’s mansion. Baxter retaliated and raised his own militia. The two militias began shooting at each other in the streets while the federal government debated whom to support.

Fast forward a few years and thousands of hours of research, and I had enough for a book about the history of constitutional crisis in America that is coming out on May 13. I argue that constitutional crises have frequently happened in American history and that they have made us into the country we are today. Although this book is relevant to the Donald Trump years, it is also about a phenomenon bigger than Donald Trump. As such, my perspective on constitutional crisis has not been skewed by a desire to promote or undermine him.

These two facts allow me to offer insight about constitutional crisis you won’t get elsewhere, particularly from commentators or publications reacting to the news of the day. If you are looking for a sober and detailed analysis of constitutional crisis, this is for you.

What is a Constitution?

Before defining “constitutional crisis,” we must answer an even more basic question: What is a “constitution”? After many years of teaching, I have discovered that even very bright law students don’t always have a ready answer to that question.

For many of them—and other students—a constitution is a set of rules to memorize and apply on a final exam about how the government works. And true enough, constitutions provide basic rules about how our government and society are supposed to operate. But they are so much more. Constitutions are statements of our dreams, fears, and values. They are stories about our country and the breathtaking journey it has taken. That means constitutional law isn’t just for Supreme Court justices or lawyers. It’s for everyone.

Around the same time Americans adopted the Declaration of Independence in 1776, they wrote America’s first state constitutions. These first state constitutions inspired the U.S. Constitution in profound ways. And they took on big questions that we are still struggling with. The Declaration of Independence is famous for saying:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

But what is “liberty”? What does it mean to say that we are all “equal”? Who counts as an “American”? How do we prevent tyranny? When is violence justified as a method of pursuing change? The fact that the men who drafted these founding documents were property-owning white male Christians makes some of us fail to appreciate how diverse the founding generation was and how much they differed over these questions. Early Americans vehemently disagreed over the proper role of women, how to raise children, and whether a country founded on ideals of liberty could have slavery. They all wanted to avoid tyranny, but couldn’t agree on how to do it.

Early state constitutions were divided about whether racial minorities could vote, whether to sanction slavery, and how much power to give elected officials. The U.S. Constitution reflects these disagreements. Delegates allowed the slave trade to continue until 1808 and counted slaves as 3/5 of a person for representation in Congress, but refused to use the word “slave” in the text. If James Madison is to be believed, Alexander Hamilton wanted the president to serve for life and viewed the English monarchy as a role model for an American executive. Thomas Jefferson wanted strict term limits for the president. The U.S. Constitution initially made space for Hamilton’s vision by refusing to impose term limits on the president, giving him a veto, and not forcing him to share executive power with a council as some early state constitutions did.

However, George Washington set an important precedent by stepping down after two terms, a norm the 22nd Amendment codified in 1951.

Since the founding, almost all states have rewritten their constitutions—Louisiana has the record with 11 constitutions. The U.S. Constitution has been amended 27 times. Its text bears evidence of how we have evolved over the past 250 years. Think of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery or the 19th Amendment guaranteeing female suffrage. American Constitutional law in 2025 reflects two great truths. First, many of our constitutional disputes are based on unresolved tensions from the founding. Second, the basic rules and expectations about society that our constitutions are supposed to reflect are constantly changing. That causes conflict.

What is a Constitutional Crisis?

Now that we have a better handle on what a constitution is, we are ready to define what a “constitutional crisis” is. I would describe a constitutional crisis as a particular moment when our constitutional order is at serious risk of collapsing.

As an analogy, consider the body’s physical health. A medical crisis occurs when an event places the person at serious risk of death or life-altering injury. Sometimes, a medical crisis happens because of a sudden event, say a gunshot wound. In other cases, longstanding health issues eventually result in a medical crisis. Think of someone struggling with high blood pressure and cholesterol for several years finally suffering a heart attack and dying.

So it is with constitutional crisis. Sometimes, an event like an unanticipated terrorist attack or an official suddenly using violence to purge political opponents could cause a constitutional crisis. However, a constitutional crisis may have long-term causes like extreme polarization or unresponsive political institutions.

What Has Constitutional Crisis Looked Like in American History?

As I argue in my forthcoming book, constitutional crises have been common in American history and have transformed American constitutional law. There have been three common types of constitutional crisis in American history.

The first is a contested election resulting in violence. In retrospect, the 1800 presidential election was one of the most important in American history. That is because John Adams and the Federalist Party conceded that they had lost and allowed their political opponents to take control of the government. That set a vital norm for a new republic. But the transition was rocky. Aaron Burr and Thomas Jefferson tied in the Electoral College. It took the House of Representatives 36 ballots to select Jefferson. While the process unfolded, two states began preparing their militias to intervene on Jefferson’s behalf, and rumors of civil war spread. That never happened. But future election disputes would descend into violence.

For example, after Kentucky’s 1899 gubernatorial election, William Goebel and William Taylor claimed to have been elected. After a prominent newspaper editor demanded to “stop the steal,” the legislature debated whether to overturn the Election Board’s finding that Taylor won while armed Kentuckians supporting both candidates swarmed Kentucky’s capital. The legislature cited fraud and bribery as reasons to overturn the election. Goebel’s triumph was short-lived: an assassin shot him, and he died shortly after taking the oath of office. William Taylor fled to Indiana and never returned to Kentucky.

The second is a conflict over constitutional identity. Our state and federal constitutions reflect our fundamental values and shared identity. One frequent conflict throughout our history is who gets to vote. Almost all states imposed property requirements to vote at the founding, but these became seen as unfair as the 19th century unfolded. Rhode Islanders disenfranchised for having insufficient wealth pleaded with government officials to recognize their right to vote. When the government refused, they responded by holding their own constitutional convention in 1841, raising a militia to implement the constitution it produced, and attacking a state armory building in 1842. Newspapers nationwide avidly reported the Dorr Rebellion while the federal government publicly debated whether to intervene.

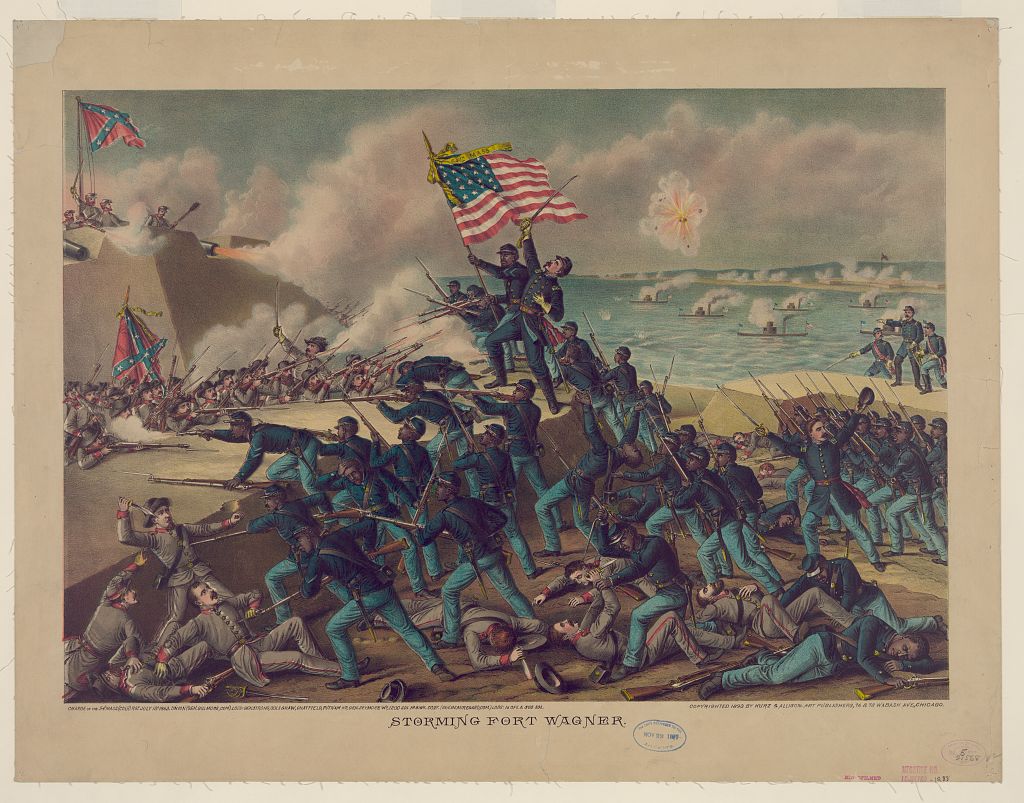

Perhaps the biggest constitutional conflict has been over race. Do the Declaration of Independence’s lofty promises of “liberty” and “equality” apply just to whites or to racial minorities as well? The Civil War and Reconstruction were about the place of Black people in our constitutional order. Southern states seceded because they were committed to maintaining Black slavery and believed the Republican Party would force racial equality on them. Racial divisions directly inspired a constitutional identity crisis so bad that Americans put on different colored uniforms and shot at each other for four years. The result was at least 600,000 dead.

During Reconstruction, southern states, with considerable participation from Black delegates, wrote new state constitutions promoting racial equality. These constitutions allowed Black men to vote and hold office.

Former slaveholders and white supremacists never accepted these constitutions. They formed the Ku Klux Klan and Red Shirts to drive Black men out of the political process. Their putsches were ultimately successful, and they overthrew Republican and Black governments in the South while the federal government looked the other way.

South Carolina’s experience during Reconstruction illustrates the third type of constitutional crisis, one that combines disputed elections and disagreement over constitutional identity. A former Confederate general devised a plan for Red Shirts to steal the 1876 election so that the Democratic Party’s platform of white supremacy could prevail in a state with a Black Republican majority. Every Red Shirt was charged with keeping a Black man from voting. The Red Shirts held parades in broad daylight to intimidate their political opponents. They murdered Black legislators and ordinary Black voters. And during the election, some white men voted twenty times.

The result was an election dispute, with neither side agreeing on something as basic as how many votes were cast. Democrats formed their own legislature, inaugurated their own candidate, Wade Hampton, as governor, and started passing laws. Republicans inaugurated their preferred candidate, Daniel Chamberlain, as governor and passed laws of their own. In a divided opinion, the South Carolina Supreme Court decided in Hampton’s favor. Both Chamberlain and Hampton personally pleaded their case to President Rutherford Hayes. Chamberlain retired from the contest only when it was clear the national government had abandoned him.

South Carolina’s experience shows you how fragile democracy is. It can fail in the future because it has failed in the past.

What’s Next?

In my next essay, I will lay out the biggest threats of constitutional crisis on the horizon and explain whether I think we are in a constitutional crisis now. In the meantime, if you find this topic interesting, consider reading Sedition: How America’s Constitutional Order Emerged From Violent Crisis, which discusses our history of constitutional crisis in much more detail than I can here. In addition, I will be giving a free virtual talk about the book on May 15 at 8:00 P.M. The event will be small so that people have an opportunity to ask questions, so sign up as soon as you can! You can order the book from Amazon or NYU Press. Those ordering from NYU Press can get a 30% discount with the code: NYUAU30.

Starting on July 1, Marcus Gadson will be an Associate Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill. Follow him on X.